Officer-involved shootings almost always deemed justified

COLUMBUS, OHIO -- Gun in hand, the officer ran between houses on the South Side, chasing a man who’d just tried to hit another officer with a stolen car and now was running away.

Officer Anthony Sebastiano was running at full speed when he saw David Richardson slow and reach toward his waistband. Richardson locked eyes with the officer, who thought he was going to get shot for the second time in less than 18 months.

“At that point, it was my understanding that he had already hit an officer,” Sebastiano told an investigator two weeks after the Aug. 30, 2012, shooting. “It just seemed at that point he had no regard for anybody’s life.”

In fear for his own life, as he later told a detective, Sebastiano fired one shot at Richardson. He missed, then fell. Other officers found and arrested Richardson about 100 yards away. He didn’t have a weapon.

Almost a year later, an internal-review board ruled that Sebastiano made the wrong decision, according to Columbus Police Division policies. The commanders on the review board voted 2-1 that he should not have pulled the trigger.

The policy they cited says that officers can use deadly force only when it’s reasonable to protect themselves or others from imminent death or serious physical harm.

The commander in the minority said Sebastiano made a “split-second decision during a tense and rapidly evolving situation.” But the chain of command agreed with the majority, and Sebastiano was suspended without pay for 16 hours.

Such an outcome — a decision by police brass that an officer wrongly fired at someone — is rare. Since 2004, Columbus officers have been involved in 174 shootings. Of the 160 in which there have been rulings, all but 10 have been ruled within policy. Fourteen others have yet to be ruled on, the oldest from April 2013.

“That’s a good grade,” said Deputy Chief Ken Kuebler, who oversees the firearms-review board. “ It’s reflective that our officers make very, very good decisions under very, very challenging circumstances.

“It’s the toughest decision in any occupation in America — whether to shoot or not.”

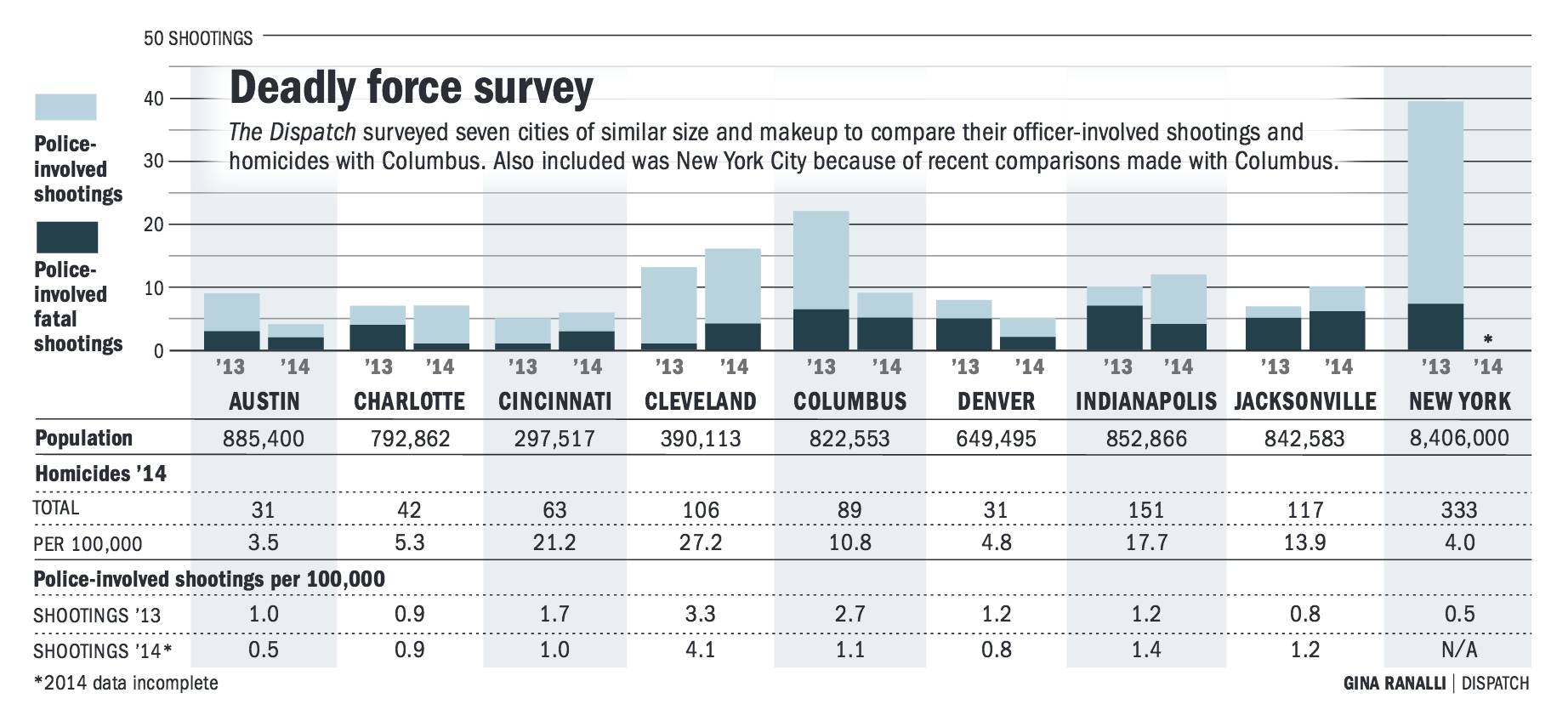

Critics have compared the 22 fatal shootings in Columbus in 2013 to the 40 in New York City that same year. But the nation’s largest city and Columbus are very different. The homicide rate in Columbus — 2.7 slayings per 100,000 people — was nearly triple that in New York in 2013. And New York — densely populated, with areas of very high income — is different from sprawling Columbus, meaning that officers work in vastly different environments.

“Your homicide rate is twice as high. It’s important to take into account the threat environment (that) officers are in,” said David Klinger, a former police officer turned criminology and criminal-justice professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Of seven cities surveyed by The Dispatch — all similar in size to Columbus — Columbus had the second-highest rate of police shootings, both fatal and nonfatal, in 2013. Last year, the city ranked fourth, at 1.1 shootings per 100,000.

Of the three major cities in Ohio in both years, Cleveland had the highest rate of officer-involved shootings — 3.3 per 100,000 in 2013 and 4.1 in 2014. Cleveland also had the highest homicide rate last year, with 27.2 killings per 100,000 people.

• • •

The Columbus Police Division, like many other departments, reviews all of its officer-involved shootings. After each shooting, a team of homicide detectives, called the Critical Incident Response Team, is assigned to investigate.

If an officer kills someone, a grand jury first reviews the shooting to decide if the officer is criminally liable. No officer has been criminally charged in a fatal police shooting in the past 18 years.

After the grand jury, and after any criminal charges against the person shot are resolved, the firearms-review board gets the case and decides whether the shooting was within policy.

Nobody was killed in any of the 10 shootings ruled bad by the division since 2004. In only two was someone shot. In six cases, the officers missed, and in two others, the suspects took off and were not found.

Related content: Unjustified officer-involved shootings in Columbus

Deciding whether a shooting is acceptable is a tough call, said Jason Pappas, a Columbus officer and president of Fraternal Order of Police Capital City Lodge No. 9.

Even commanders, with months of hindsight, sometimes can’t agree, he said. At least one of the bad shootings was a split decision. Sometimes, the chain of command overrules the board’s decision.

“You have three very skilled and highly educated people reviewing the same material and can’t come up with the same conclusion,” Pappas said. “The officer had none of that (time). The officer had a split second.”

Discipline for officers ranged from 120 hours of suspension to a written reprimand or training.

“I think it’s important we recognize officers are held to a very high standard, not just with the law but with our policy, and that when we feel they’ve made a mistake, we do something about it,” Chief Kim Jacobs said.

Since 2004, 46 people have been killed by officers, and in each of those cases, the shootings were justified, the review board said.

Three of the unjustified shootings were unintentional discharges that involved a suspect, according to a Dispatch review of police records. It appears the officers did nothing wrong, but because they fired their weapon without intent, it was ruled not within policy. Starting with 2013 shootings, in addition to a ruling of “within policy” or “not within policy,” a shooting also is classified as “intentional” or “unintentional.”

The biggest complaint from those within the division, from the chief down, is the time it takes commanders to review a shooting — as long as two years, in some cases, because any criminal case needs to be completed before the administrative review begins.

• • •

Recent high-profile officer-involved shootings nationally have focused attention on how the cases are handled, and some people have called for changing the review process here — most notably, by adding a civilian component.

“Currently, there’s a conflict of interest,” said Timothy Singratsomboune, an Ohio State University senior who helped organize two marches to police headquarters last year, demanding changes. “If I’m expected to find myself guilty or innocent, which one do you think I’m going to pick?”

Though police-involved shootings are rare in Columbus and nationally, “they’re important enough that they warrant additional scrutiny by outside civilian forces,” said Brian Buchner, the president of the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement.

Buchner is a special investigator with the office of the inspector general at the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners. One purpose of the commission — essentially a civilian board of directors — is to assure the public that internal investigations are fair and proper, Buchner said. And even with civilian oversight, the majority of police shootings in Los Angeles are found within policy.

“The public can gain more trust in the investigation and in the outcome, and ultimately in the police department,” he said.

Kuebler said that trust already exists between Columbus police and the community. Civilian oversight here, he said, is the mayor, the safety director and the city council. Grand juries consist of civilians, and almost all completed investigations are available through public-records requests.

“I think our track record goes a long way,” Jacobs said. “I think we have a very, very good relationship with the community overall.”

Singratsomboune isn’t convinced: “Why shouldn’t citizens have a say in their own safety?”

• • •

In the past month, The Dispatch attempted to contact all of the more than 200 officers involved in a shooting since 2004 via email and through the division.

Only two officers agreed to an interview — former partners James Howe and Adam Hicks, both 36 years old and 14-year police veterans. Between them, they’ve been involved in five shootings, two when they were partners.

“Just bad luck,” said Howe, now a third-shift homicide detective.

One of the shootings was fatal. None was ruled outside policy.

The shootings happened so fast, there wasn’t time to think, and as cliché as it sounds, training took over, both said.

Although they knew what to do in the midst of the confrontation, it was less clear afterward, both said.

In one shooting, Howe said, a member of the officer-support team had to remind him to call his wife to say he was OK. “Your mind is scrambled,” Howe said.

Both believe the Police Division procedure works well: a few days off, a psychiatric evaluation and back to the beat if the officer feels ready.

In two cases — one involving just Hicks and the other involving both men — a civil lawsuit was filed by the person who had been shot, but both suits were dropped.

Both officers acknowledged being frustrated while waiting for the review board to investigate. And the Monday morning quarterbacking is not fun.

“It’s easy to look at it from afar after a few days when everything is spelled out for you,” Howe said. “But walking into a fast-evolving situation ... it’s just a split-second decision.”

Questions from friends and attention from reporters can make for “a pretty miserable situation,” Howe said.

The last two shootings Hicks was involved in were just six months apart in 2008. The last incident, the nonfatal shooting of a teenage girl who was carrying a pellet gun, generated a lot of attention and controversy.

“I knew I’d done the right thing, and I went with that in my mind,” he said. “You made it home. That’s the main goal.”

As a detective, Howe is off patrol now. But for Hicks, still in the patrol bureau, there’s always a shadow of a doubt about what the next run might involve.

“Do they normally end up good?” Hicks said. “Yes ... but you never know what’s going to happen when you get there.”